Guides to Archives and Digital Resources

NYCTC members have visited countless archives and used countless digital resources in the course of our research. Below are short descriptions and guides to archives and digital resources of use to historians of modern Britain and the British Empire, written by past and present NYCTC members and our friends and colleagues.

Boots Company Archive

Last Visited: Autumn 2014

Location: Boots Corporate Offices in Beeston (outskirts of Nottingham)

Opening Times: Appointment only: email judith.wright@boots.co.uk

Boots have a comprehensive business archive that they are keen for academics to use and that is well-indexed. You can photograph material. The head archivist, Judith Wright, is extremely knowledgeable, an advocate of business history and business archives and very helpful over email and in real life. The archive contains a lot of company reports, policy stuff on their tangential relationship to the NHS, and probably all sorts of other stuff (I was just there to look at their attitude towards shopping centers and shopping spaces—there was some interesting material but not a huge amount for me).

It’s hard to get to. You have to go to Beeston train station. I got a cab from there (I think it’s about an hour’s walk?). It’s located right in the middle of the vast corporate Boots compound. A kind of company town—an interesting if deeply bleak place. I seem to remember there was a cheap café on site.

—Sam Wetherell

Department of Special Collections, Cambridge University Library

The official University Archives and the archives of most of the faculties are held here (among many other things). You need a UL reader’s card to get in the UL; if you’re not a member of the university, you can turn up on the day and apply for one, or apply in advance online through the library website. ID and proof of address is required. Postgraduate students and researchers at other UK universities are entitled to a card for free, as is anyone who is only using special collections material; overseas researchers who wish to use the modern collections can pay £10 for a six-month card or £20 for a twelve-month one. Bags and coats are left in a locker room at the entrance to the UL. In the special collections reading room, there are many desks. You request items by filling in paper call slips and turning them in to the front desk. In my experience the staff are friendly. I have a minor obsession with the UL tearoom, which serves hot and cold lunch food, coffee and tea, and more or less anything else you could want.

— Emily Rutherford

Corpus Christi College, Oxford

Corpus is a small college in centrally-located Merton Street. Its special collections department is chiefly known for its early modern books and manuscripts but they also hold some fellows’ papers and of course the college archives. The archivist and assistant archivist are both part-time and the archive is normally open three days a week, but they can sometimes move things around to accommodate your schedule if you are very nice. There are only two places for readers so it’s necessary to book in advance. You will register in the library office in the main (16th-century, very interesting historic etc.) library, then go across a quad to a cramped, freezing basement strongroom where you will be sat at a desk directly opposite the archivist, who will watch you while you read. There is a locker in a room outside the basement where you leave your bag, and there are toilets and water on this staircase but unfortunately they require being let out of and back into the strongroom. Photography is allowed but you have to fill in a copyright form. The archivist, Julian Reid, is worth getting to know; he is extremely knowledgeable about college and university history and the extent of the collections here and at other colleges.

— Emily Rutherford

Derbyshire Record Office

Last visited: April 2018

Opening times: Monday: Closed; Tuesday to Friday between 9.30am and 5pm; Last Saturday of the

month between 9.30am and 4pm.

This is a fairly standard county record office, presumably with the sorts of documents you would expect to find in such an archive. The record office itself is not in in Derby, but rather in the picturesque village of Matlock, which is around half an hour on the train from Derby, and within walking distance from the station.

Once you’ve found your way through Matlock’s streets and up the very steep hill to the record office, your reward awaits you outside and in. Before you enter, your position atop a hill provides you with a gorgeous view of the Peak District’s green hills, and a large tinted window in the reading room allows you the same view without any glare from the sun.

As this is a county record office, you will need a Record Office Reader’s Ticket, which you can obtain with photo ID and proof of address at most (but not all) county record offices, which in turn provide access to the majority of county record offices across England. The office itself looks as though it’s been recently renovated. Resources available to researchers include a reading room where documents, collected by staff once an hour, can be consulted and photographed (if you’ve purchased a photography pass at £5 per day) and a computer suite for perusal of the archival catalogue as well as your own work. Lockers are available upstairs, as is a communal room for rest and refreshment. When I visited, the reading room closed between 12:00 and 13:00, though said visit was on the last Saturday of the month so I can’t be sure that this is standard practice. Signs in the reading room suggested the presence of a café upstairs, though this didn’t seem to be there on the Saturday I was there. It’s only a short walk, no longer than five minutes, down the hill into Matlock itself where refreshments can be purchased (experience allows me to recommend no more than the Greggs…), but there is amble space for researchers to spend time outside the reading room if they have brought their own lunch.

The index of this record office seems fairly comprehensive, but friendly and informed staff are on hand to help.

–George Severs

English Faculty Library, Oxford

The EFL is a mid-century modern building on St Cross Road, maybe 5-10 minutes’ walk east of the Bodleian. It is mostly a student library with a teaching collection but holds a small number of modern literary manuscripts, which are listed in the main Bodleian manuscript catalogues. If you have a Bodleian reader’s card you can enter through an electronic gate, and speak to the person at the enquiry desk to order what you need. You can turn up during term, but in the vacations— particularly the summer—there are reduced opening hours, so you should book in advance. There isn’t a reading room; they’ll sit you down at a normal desk within view of the enquiry desk, and I don’t recall there being any security about bags etc.

Hatfield House Archives

Hatfield is very professional for a country house archive, since this is the archive of the Cecils. Lots of researchers have used these collections, including e.g. Andrew Roberts for his biography of Lord Salisbury. The archive is in the basement of the house itself, and there were two archivists present both days I was there. They were knowledgeable about the collections and helpful in producing material. Hours here are a pain. I don’t recall quite what they were, but between opening late, closing early, and closing for an hour at lunch (you’re stuck at the café with the tourists), you’ll be lucky to do five hours’ work. Bring a novel.

I booked a hotel and stayed in the town, but this was a mistake. Hatfield is about 20 minutes from Kings Cross, and it would have made more sense to just take the train back and forth – especially since the town is pretty ghastly (roundabouts, malls, traffic islands, underpasses). I tend to walk everywhere, but at some point I sort of clocked that it didn’t make much sense for me to be tramping through dank underpasses frequented by the local youths looking vainly for my (totally indifferent) hotel. Hatfield House, or at any rate the avenue up to the house, by contrast, is basically right across from the train station.

— Susan Pedersen

Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies

I went here to use the papers of Ettie Desborough, one of the great country-house hostesses and aristocratic correspondents of the late Victorian through interwar period. There’s no reason for me to write this up at length, though: they have a perfectly competent website listing hours, access, and everything else you need to know (except that you should bring your lunch, as the archive doesn’t seem to have anything but machines with coffee and candy bars). As always, I walked from the railway station; it’s about 20 minutes. They have extensive holdings, including the massive Desborough papers. The archivists are helpful, although the lead archivist does talk loudly on the phone in the reading room: if this will bother you, bring earphones. (I’ve found this is ubiquitous behavior among archivists who have come to essentially “own” a small archive; the archivist for the League of Nations records was lovely and helpful but basically treated the reading room like her living room and had long conversations in French about all and sundry while the two or three researchers were trying to work. We rely on them, so can’t really complain: just live with it.) They’re easily reachable from London and closed Mondays.

— Susan Pedersen

Inverary Castle Archives

Inveraray Castle has a great, great, archive, located in a climate-controlled room in the Estate Office. This is the personal archive of the Dukes of Argyll going back a few hundred years. If one wanted to write about the Clan Campbell, and about the management of the very, very extensive Argyll estates across the last four centuries, this would be where you’d go. (I didn’t use those records.) Holdings for the eighth Duke (a critically important Whig-Liberal politician, who broke with Gladstone over land questions and home rule) and the ninth Duke (the Marquis of Lorne, Governor General of Canada) are especially complete. (The ninth Duke married Princess Louise, daughter of the Queen Victoria, and there is quite a lot of Royal Correspondence because of this marriage; it is easier to access that material at Inveraray than through the Royal Archives.) The collections are decently catalogued (although there are two, overlapping, catalogues), and – helpfully – a good portion of the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century family correspondence was carefully copied out in a clear hand by the tenth Duke, who was rather retiring but had a passion for family history. I’ve checked some originals against his copies (both are in the archive) and he seems to have transcribed properly and without excisions.

I used the archive when they were “between archivists,” but they now have a new archivist, I believe full time. Getting to the archive isn’t difficult, but it’s good to set aside time. The Estate Office is about ten minutes’ walk from Inveraray Castle (full of tourists, and has a café); both are about fifteen minutes walk from the town of Inveraray, a lovely, small eighteenth-century planned town. Inveraray has no rail link (vetoed by the 8th Duke), so you need to either drive or take a bus (c. 2 hours) from Glasgow. The town has a few perfectly good and inexpensive hotels: I stayed at Brambles; clean, spacious, great breakfast. There are a couple of decent and one very good (Samphire) restaurants. Bring novels as there is absolutely nothing to do there after dark.

— Susan Pedersen

The Keep, Sussex

Last Visited: September 2018.

Location: 10-15 minutes’ walk from Falmer train station.

Opening Times: Monday: Closed; Tuesday: 9.30am – 5pm; Wednesday: 10.00am – 5pm; Thursday:

9.30am – 5pm; Friday: 9.30am – 5pm; Saturday: 9.30am – 4pm (Reading Room closed 1-2pm).

Access: Bring two forms of ID with you.

I recently visited The Keep in East Sussex to use a series of their collections relating to the history of Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988, which prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities. The Keep houses the East Sussex Record Office (ESRO), the Royal Pavilion & Museums Local History Collections, and the University of Sussex Special Collections. Many of us will be familiar with The Keep as it houses the Mass Observation archive, and historians of sexuality in modern Britain will be aware of its LGBT history collections, including the Brighton OurStory Collection and the National Lesbian and Gay Survey.

The Keep is located near the University of Sussex. If you travel by train from Brighton to Falmer train station, you then need to walk 10–15 minutes in a straight line (coming from Brighton, you need to cross over to the other side of the platform and take the path which leads away from the Amex stadium). Directions can be found on The Keep’s website. If driving, there is a pay and display car park.

A few things to consider before you go: 1) the train line into Brighton has been affected by strike action and engineering works over the past few years, making it somewhat notorious. It was fine when I traveled, but do check before you set out. 2) There is no café at The Keep, just a vending machine. Its website says that there is one 5 minutes away—this is closed. You could walk 15 minutes to the University of Sussex campus, but it is much more advisable to bring lunch with you. 3) I found that with several of the collections I was using, the archivists will only hand out ten documents at a time. If this is proving frustrating and/or time-consuming, they will allow you to go through the box at the desk to figure out what you want to consult, so just ask. 4) A photo pass is £12 per day or £30 for a week, which is pretty steep so plan your photography carefully if possible! No need to book an appointment, but it’s worth registering online first and making a “wish list” of what you want to consult as this greatly speeds up the process when you’re there (and you’ll have to do it once you’ve arrived anyway).

— George Severs

King's College Archive Centre, Cambridge

I have been to King’s to read the personal papers of old members and the records of the Apostles essay society. King’s is in the center of Cambridge and impossible to miss. They have a modern, spacious reading room with about 10-12 places for readers. It’s necessary to book your place in advance. The reading room is inside the college library, which is in the second court. You have to enter at the main entrance on King’s Parade and tell the custodian at the gate that you’re going to visit the archive (sometimes they call up and check) and then you go through and ring a buzzer to get into the library building, and the special collections reading room is up a couple flights of stairs. Once you’re inside there are toilets, water, etc. accessible inside the library. The first time you come, you fill in a registration form with your details. They’re pretty low-security within the reading room, and just ask that you place your bag in a corner of the room away from your desk —though there can be certain privacy restrictions with respect to some of the collections (I’ve experienced this with the Apostles papers) and photography is, unfortunately, prohibited. You fill in call slips and the store is right behind the archivists’ desk, so requests come right away. The archivists are extremely friendly and helpful.

— Emily Rutherford

Knebworth Archives

Knebworth is the Lytton house. It is about twenty minutes from King’s Cross, but you’re best advised to go to Stevenage, as there are lots of trains and there is no, repeat no, way to get to the house except by taxi from the station. An impenetrable perimeter wall surrounds the whole estate. Entry is through a security gate operated not by a human but by an intercom system: you need to have the taxi ring and they’ll buzz you in. The archive here is in the Estate Office (go LEFT at the end of the long, long driveway when you have the house in front of you). Taxis almost always deliver people instead to a conference facility behind the house on the right (this happened to me) and you will be stuck trying to find someone who can point you in the right direction and then tramping across the estate to the Estate Office, which is tucked behind the house on the left across a cattle grid. Unless you bring lunch (which I had the good sense to do), you will be stuck tramping back to that conference center, which has chips-and-whatever type food. (Knebworth is catering to local families bringing children to an adventure playground or petting zoo or something of that sort, more than to the house.) Figure out in advance, too, how you will get out of this place: I had real trouble getting taxis to come pick me back up, as they have to go through that perimeter security system; for two of the three days I was there, the archivist nicely just took me to Stevenage at the end of the day, but this surely isn’t her job and can’t be expected. Good luck.

The Lytton papers for the earlier periods have been sent to the local record office; what is still at the house are the papers of Robert Lytton, Viceroy of India and poet (under the name “Owen Meredith”) and his daughters, including Betty Balfour, Emily Lutyens and Constance Lytton (the suffragette, who accounts for most of the traffic the archive gets). Now, this isn’t an “archive” in the full sense of the term: it is a record room stuffed with boxes on shelves, with three desks crammed together under the eaves – two for two staff members and one for a researcher. The archivists are part-time and come in one or two days a week, which is when you can go too. You must, then, be in touch with the archive well in advance to book a day and explain what you need. The archivists are accommodating and know the archive well, and they have a catalogue, but be sure you consult the old hand-written index cards listing (say) correspondence as well as their online catalogue, as the latter are more complete. The current Lord Lytton would like to reconstitute the whole family archive and build a purpose-built facility for it, but whether there will be funds for such a venture is anyone’s guess. He is writing some family history, and is very civic-mindedly keeping the records available.

— Susan Pedersen

London Metropolitan Archives

Last Visited: Summer 2016

Location: City of London, ten minutes’ walk from Angel Station

Opening Times: Monday-Thursday (don’t forget, like I did, that it’s closed on Fridays…)

Access: Bring photo ID.

This is a big archive that lots of people have different experiences of, so I welcome other voices and ideas on this one. The archive contains records produced by the City of London, the LCC, the GLA (I think), and the MBW as well as various other collections that I haven’t used. I went there to look at material relating to the construction of the Boundary Estate and the regulation of a handful of markets in the late nineteenth century. You have to use their slightly infuriating online search system which others probably have had better or different experiences with to me. You fill in a paper slip and can make three requests every 45 minutes. The staff are helpful if slightly long-suffering. Be prepared to wait in line behind family historians.

When you enter you have to leave your stuff in lockers on the (UK) first floor, then go up to the second where you register and make requests. The searchrooms are bright and you can take photographs. They are also heavily air-conditioned, so bring warm clothes even if it’s the peak of summer—one of my abiding memories of the archive was being really cold in the middle of summer. The archive is ringed by nice if expensive hipster cafés and there’s a nice park to have lunch in. It’s also right next to Exmouth Market which has a nice street food thing going on.

—Sam Wetherell

Sainsbury's Archive

Last visited: Autumn 2014

Location: Museum of London Docklands, London

Opening Times: ONLY ON THURSDAYS

Visiting: By appointment only

The Sainsbury’s Archive is the company archive of Sainsbury’s. It is one of the best business archives in the country and is an amazing resource for those interested in urban space, the service economy, nutrition and food, philanthropy, etc. I got the sense that they were over-staffed and under-used—the archivists were delighted to have an academic historian visit (usually it’s just hobbyists, people interested in design, or other business people). Photographs are permitted. The location is easy and pretty spectacular—it’s a short walk from Westferry DLR, right in the middle of the Docklands skyscraper-y complex, and the archives are nestled deep in the Museum of London Docklands (you have to walk through the exhibits to get there). There is an adequate and predictably-priced café on site.

It’s also worth noting that the same archive also holds the records of the Port Authority of London, the London Docklands Development Corporation and various interesting grassroots anti-gentrification groups in East London (the “Docklands Forum” being the biggest).

—Sam Wetherell

Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville is in St Giles, 10-15 minutes’ walk north of the center. It holds college archives and certain key collections of fellows and old members. I have read the Margery Fry papers here. The archivist is only on duty Tuesdays and Wednesdays and there are only places for two readers, so it is essential to book well in advance. The reading room is a seminar room within the college library. You fill in call slips to get what you need and the archivist will leave you alone while you read. You can have your bag in the room but not at the table, and there are toilets on the same corridor as the reading room. Photography is prohibited. The staff are very friendly, but the restricted opening hours are a pain.

— Emily Rutherford

St. Anne's College, Oxford

St. Anne’s is on Woodstock Road, some 25-30 minutes’ walk north of the center depending on where you start. It holds some significant papers relating to the history of women’s education in Oxford, but does not have a special collections department or dedicated archivist. When I visited (making an appointment in advance) I was helped by the college librarian and his assistant, who sat me at a desk in the student library and fetched stacks of disorganized paper from a random cupboard. There is a small card index in a box which offers a vague guide as to the contents of the collections. Photography is allowed.

— Emily Rutherford

Trinity College, Cambridge

I have been here to read the papers of fellows of the college. Trinity is in the center of Cambridge and impossible to miss. Students use a modern library; the Wren Library is the old (very beautiful) library which now houses special collections. It’s a very long gallery with a narrow central aisle lined with book presses, mostly in the dark, and readers sit at a table with about six places at the end of this long aisle, which is certainly atmospheric. You need to book a place in advance, and fill in a registration form when you arrive—and I think you need to present ID. You fill in call slips and the archivist goes to fetch things for you. Because it’s such a small table the archivist tends to hover over you and watch while you read, but is otherwise friendly and helpful. Photography is allowed but you have to fill in a copyright form. I was here a while ago, but I recall that you had to leave your bag in a locker outside, and that toilets were not terribly convenient to the reading room.

— Emily Rutherford

Wellcome Library

* Archives: Wellcome Library.

* Date of last visit: 24 April 2016.

* Accessibility: the Wellcome Collection (the building which houses the library) is round the corner from Euston Square tube station. Euston Station proper is across the road; Kings Cross/St Pancras is about ten minutes walk away.

* Food situation: the Wellcome Collection has a reasonably priced (by central London standards) café with good coffee. There are water dispensers within the library.

* Catalogue details: the library’s main catalogue is online and well-organized. Some items in the library’s collection have been digitized and can be consulted online by library members without going to the library! Ordering material is very easy: most items can be ordered online in advance of your visit, though there are a few collections which must be ordered in the archive, with a paper slip.

* Archive policy and any other relevant details: bear in mind that while most unpublished items can only be consulted in the manuscripts room, published material will likely be delivered to collect from the library desk. If you have some spare time waiting for a delivery, the Wellcome Collection puts on good exhibitions in the history of medicine which are worth looking at.

Weston Library, Oxford

The new Weston Library—in Broad Street opposite the old Bodleian buildings—is enormous but relatively easy to use. There are two entrances—one for the public and one for readers—and you can apply for a Bodleian reader’s card in the access office just to the right of the public entrance. If you want to save time, you can fill in and print the paper forms ahead of time, which require you to enumerate which archival collections you intend to access. Cards are free for UK researchers, alumni of the University, and those who are only accessing Special Collections material, but there are substantial fees for overseas visitors who wish to use the normal library collections. There is lots of space in the reading rooms and you don’t necessarily need to book a place in advance, but you might wish to during particularly busy periods such as in high summer. You leave your bag in a locker room at the readers’ entrance, and then you use the card to go through an electronic gate to access the reading rooms, which are upstairs—there are also toilets and a water fountain on the staircase. There are rooms designated for rare books and western manuscripts, non-western manuscripts, and maps, but you can work in any of them.

At the entrance to the reading room, you need to sign in with a porter. If you step out of the reading room briefly, you can usually leave your materials at your desk, but you might need to leave your reader’s card with the porter. Most modern western material has been catalogued and can be requested to the reading room electronically through the online catalogue, but some things are not yet in the online catalogue and may have to be ordered by paper call slip. If a collection isn’t in the online catalogue, there are paper indices available in the reading room and in digitized form through the library website which you can use to find the shelfmark—and these can sometimes be easier to use than the online catalogue, anyway. An archivist can explain how this works to you, or I can. The staff at the Bod are unfortunately not the friendliest or the most tolerant of young Americans who don’t know what they’re doing. There is a tearoom on the ground floor next to the readers’ entrance, where they have cold lunches, cakes, and coffee/tea—at considerably subsidized prices relative to those in the Bod cafe that’s open to the public.

— Emily Rutherford

Kindred Britain

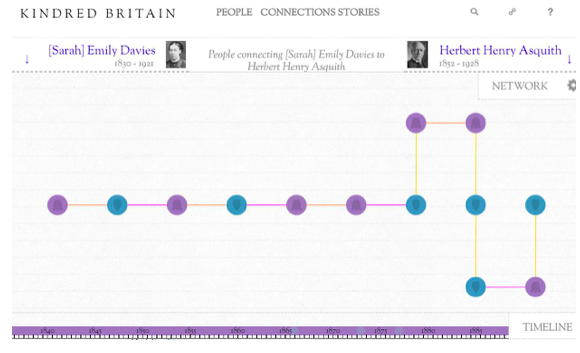

Kindred Britain is an ambitious attempt by Stanford University to provide a means of visually representing the relationships between prominent figures in culture and arts, politics, science and engineering, the military, and other sites of influence. It offers mini-biographies of around 30,000 individuals, and allows you to trace connections of kinship, ancestry, and marriage. The range is potentially across sixteen centuries, though in practice most data spans c. 1700-1950. The major emphasis is on the nineteenth century, due to the use of the Dictionary of National Biography. One of the niftiest elements here is that you can trace such connections across multiple degrees – for example, Florence Nightingale and George Orwell can be connected by her maternal aunt’s marriage into the Bonham Carter family, who then married into the Lubbocks, who married into the Pitt-Rivers, whence came Orwell’s wife Sonia Brownell. Now, this kind of connection is so distant as to be barely meaningful. But it does give a visual sense of the deeply connected realms of family, influence and knowledge production in Britain. Each individual or relationship can be set into a timeline of different lives and events, and into a map that charts places relevant to the selected individuals.

The potential here is fantastic—Kindred Britain can point to unnoticed connections via siblings or the “lattice” of the family, which helps put the usual networks of intellectual history based on ideas and ideology into another context. It offers a condensation of some of the strengths of family history, but set within a sophisticated sense of individual lives. It reminds us of spatial location, which unavoidably and helpfully brings empire into our frame. The visual nature of the site is really strong—though in practice, the different screens and views are hard to navigate.

Searches can be organized around individual names, subsections of professions (e.g. anthropologists), political affiliation (e.g. feminists), or other attributes (e.g. dandies, criminals). There’s something whimsical about such categories, but it’s deeply exciting to search for, say, all political rebels born between 1750 and 1800 associated with Greenwich. As the guidance notes state, “Kindred Britain grew through a process that involved as much sensibility as rigor.” This is a selective who’s who, inspired by Noel Annan’s idea of an intellectual aristocracy. Given its origins in an English department, Kindred Britain places literature at the heart of British society. Despite the promising categories, there simply aren’t many criminals, or feminists.

Kindred Britain does little to challenge the canon of intellectual and cultural history. Despite its broad coverage, it still invites us to look at the figures who are already understood as significant, and could lock our terms of reference into a static sense of whose contributions should be valued. Even major figures like Emmeline Pankhurst are missing. The “most viewed” function points, inevitably, to figures such as Shakespeare, Darwin, George Washington, and Virginia Woolf; our attention might never stray from their stories. I do, however, think this is a powerful research tool that can be used to offset or disrupt the canon, and to bring out surprising findings about the family tree. However, the democratic nature of family history sites such as Ancestry.com, for all their paucity of detail and visual appeal, are likely to have more potential to subvert than this beautiful visualisation of “people who matter.”

— Lucy Delap

A Vision of Britain Through Time

A Vision of Britain Through Time is an important source for historians of Britain in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries interested in locality, place, and region. Users can search the database for places by their name, postcode, or their location on a map. Once they have selected a place, users can then access selected information about its history from 1801. Information includes statistics on a place’s population and occupational structure, detail on local educational attainment and religious affiliation, and rates of illness, unemployment, and poverty. Users can also search by category of information, for instance by using the “Statistical atlas” to generate maps which compare how different areas performed on these measures, and in some cases tracking change over time.

For each place, statistics compiled from historic census reports appear alongside more recent information from the Office of National Statistics, scans of historic maps, general election results, and contemporary comments from gazetteers and travel writings. Most social histories are also local histories, at least implicitly, and the value of this resource is that it allows users to quickly build up an intensive picture of a single locality over time, integrating material from different sources which it would be laborious for an individual to put together.

However, the first-time user may find this wealth of information overwhelming. Since the project defines places by different historical administrative units, the website represents Britain by over 20,000 separate (sometimes overlapping) places. For instance, Cambridge has over 70 administrative units associated with it on the website: some of these are smaller areas within the city, not all of which have information attached to them, while others are different ways in which the place known as “Cambridge” has been defined historically. Users researching the history of a modern place may therefore have to choose between looking at information relating to an ancient district, a parish, a poor law union or registration district, or a modern local government district. Inevitably, this constrains the sort of information available for a given time period. Users interested in tracing changes in a given measure in a single place over time may therefore have to compare different administrative units covering the same place, but should be careful to note that that geographical boundaries of each administrative unit may have changed! Cambridge, as a local government district, must be nearly twice as large as Cambridge, the poor law union district. Nevertheless, the website helpfully shows what each administrative unit looked like on a map, making it a valuable source of the history of local administration.

If the sheer volume of information the website collates can make using it somewhat unwieldy, it is not a comprehensive collection of information—though it does not pretend to be. Sensible decisions have been made about which measures have been collected. Out of necessity, contemporary comments about places come from works which are out of copyright, so they are concentrated in the nineteenth century; hopefully they will be continually updated. Information on Scotland is under-represented compared to England and Wales, something the project’s creators acknowledge. Still, with historians like Helen Smith emphasizing the significance of “regionalism as a category of analysis” for much of the twentieth century, the development of resources like A Vision of Britain will help in understanding how much of people’s lives continued to be shaped by the places where they lived.

— David Cowan